THE TRADWIFE'S SECRET |

|

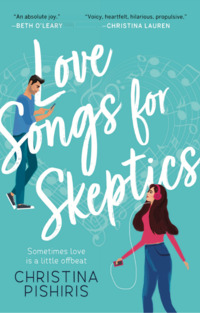

Sourcebooks Landmark Read Kindle PreviewZoë Frixos gets the whole love song thing. Truly, she does. As an editor at a major music magazine, it's part of her job description. But love? Let's just say Zoë's been a bit off-beat in that department. After falling hard for her best friend, Simon, at thirteen and missing every chance to tell him how she felt before he left town, Zoë came to one grand conclusion: Love stinks. Twenty years later, Simon is returning to London, newly single and as charming as ever, and Zoë vows to take her second chance. But, with an arrogant publicist out to challenge her career, Simon's perfect ex-girlfriend's sudden arrival, and her brother's big(ish) fat(ish) Greek wedding on the horizon, Zoë begins to wonder if, after all these years, she and Simon simply aren't meant to be. What if, despite what all the songs and movies say, your first love isn't necessarily the right one? In the wake of a life-changing choice, Zoë must decide if she's right to be skeptical about love, or if it's simply time to change her tune... Excerpt 3 Nothing Compares 2 U My alarm usually went off at 8:00, but I woke up at 7:15 feeling refreshed and full of energy. It didn’t make sense—I’d slept less than five hours. But as I lay in bed stretching my arms and wiggling my toes, it suddenly hit me. I was happy. I hadn’t felt happy in ages. The stress of my job was pulling me under. It was obvious now—why hadn’t I noticed before? One postcard, and it was as if someone had changed the soundtrack from Radiohead to Motown. Simon always had that effect on me. We grew up next door to each other, but when he’d first arrived I’d been wary. I was ten and, having lived in the noisy cocoon of an extended Greek family, I didn’t know what to make of a blond, blue-eyed only child with parents who didn’t speak to one another. My mum invited Simon over the day they moved in. Quick to notice the harassed faces of his parents as they directed the endless flow of cardboard boxes, she shepherded him out of the way of the moving van awkwardly parked in our Ealing cul-de-sac and shooed him down the side gate that led to our back garden. Mum suggested I show him our vegetable patch, so I left my bike, a Raleigh Chopper with worn-out tires, in the middle of the lawn and dutifully walked Simon to the end of the garden where my parents grew cucumbers, artichokes, marrows, and another leafy thing whose English name was a mystery to me at the time. Its Greek name, lahana, was met with a blank stare. (I later learned it was a type of chard.) The Baxters were American, but this meant nothing to me until my brother Pete appeared and went googly-eyed over the accent and wouldn’t stop asking if Simon personally knew the Dukes of Hazzard and Michael Knight. Poor ten-year-old Simon eventually said yes just to make a new friend. At thirteen years old, Pete still had that allure that high school kids held over juniors. Simon didn’t go to Hazelwood Primary School like I did. His parents—or rather his father’s engineering firm—carted him off to a posh Catholic school all the way out in Hammersmith. Unsurprisingly, he hated it there and never really fitted in. The accent, however cool Pete claimed it was, singled him out as different. So he’d hang out with me after school. For those first three years, everything was plain sailing. That was, until we turned thirteen and everything changed. Or at least it changed for me. It was around the time I bought my first bra: I went straight to a B-cup because, being a tomboy, I’d been in denial about having boobs. But my new hormones came with an added complication: I started feeling awkward around Simon. One early September day, after I’d got back from my annual four weeks in Cyprus staying with cousins, I found him leaning against the gatepost, waiting for me. He seemed taller, his shoulders wider, and it was as if a switch flipped inside me. I fancied him. Compared to the boys I’d hung out with all summer, he was James Dean. Where they were black-haired and scowling, Simon was dirty-blond and laid-back. He didn’t wear high-waisted jeans or white terry cloth socks. He wore low-slung Levi’s and Converse. “Alright, Frixie,” he called when I came to the front garden to meet him. Thank God he was acting like nothing had changed, because I was barely remembering how to put one foot in front of the other. “Hi, Si,” I muttered, not daring to look him in the eye. He stood up straight and I got a whiff of his Sure deodorant. Why was I suddenly weirded out by it? I’d been with him in Superdrug when he’d bought it, for God’s sake. “Something’s different,” he said. Terror seized me. I forced myself to look at him. Oh Christ, had his eyelashes always been that long? “What are we doing, then?” I said, ignoring his comment. He leaned closer to me, and I got another blast of his heavenly anti-perspirant. My own wasn’t doing a very good job. My armpits were distinctly damp—thank God I was wearing my black Nirvana T-shirt. He was peering at my nose and I thought: if there’s snot hanging from my nostril I will kill myself. He smiled. “Are those freckles?” I smiled back, relief washing over me. In all the teen romance books I read, the heroine always hated her freckles. But I loved mine because they marked me as normal—all my English friends had them. They were usually very faint, but the Mediterranean sun had coaxed them out. It wasn’t just my complexion that had transformed. That summer had changed me in other ways too. Maybe it had something to do with going to my first nightclub, Careless Whispers, on the Larnaca beachfront, or the first alcoholic drink I had: a San Francisco cocktail that my cousin Elena said would taste great—it didn’t. It was a cliché, but over one summer I’d experienced three revolutionary moments in my young teenage life: sex—a French kiss on the beach with Elena’s friend Demetri; drugs—I was counting the half-shot of tequila in my San Francisco; and the Marks & Spencer bra-measuring service—why hadn’t I realized I’d grown out of my bikini before I got to Cyprus? I looked indecent. No wonder Demetri was so enthusiastic. So when I got back to London, I suddenly appreciated Simon for what he was. Where I used to see a lonely, shy misfit, I now saw a misunderstood, rebellious loner. How had I not noticed how intense he looked when he flicked up the collar on his biker jacket? How could I have brushed him off when he suggested the two of us skip school to see Almost Famous in the back row of the cinema? Luckily, none of my casual rejections had affected Simon. He still called me his best friend, but now “best friend” had a hollow ring to it. I wanted more. Start Reading LOVE SONGS FOR SKEPTICS Now

Our Past Week of Fresh Picks

Don\'t miss out on the stunning DELUXE LIMITED EDITION while supplies last. This breathtaking collectible is only available on a limited first print run Read More »

“Southern bestselling sensation” (Katie Couric Media) Kristy Woodson Harvey returns with a delightfully moving new novel about a mother-daughter duo learning to Read More »

INSTANT NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLERA Most Anticipated Book of 2025: Goodreads • USA TODAY • Marie Claire &bull Read More »

She\'s right. It can never happen again. She won\'t let it.Ten years have passed, and Ren Taylor is back at square one Read More »

The New York Times and #1 internationally bestselling Department Q series comes to a thrilling conclusion when the team must turn inward Read More »

From Jess Kidd, the bestselling author of Things in Jars who “is so good it isn’t fair” (Erika Swyler Read More »

Two sisters living on Martha\'s Vineyard during World War II find hope in the power of storytelling when they start a wartime book club Read More »

SHE\'LL BURN BRIGHT ENOUGH TO RIVAL GODSSeparated from everyone they know and love, sworn warriors (and warring allies) Bellanca and Carver are on a Read More » |

|

| |||

|

||||

© 2003-2025

© 2003-2025