BURY OUR BONES IN THE MIDNIGHT SOIL |

|

Lucy Stone Mystery Series, #7 Tinker's Cove has a long history of Thanksgiving festivities, but this year someone adds murder to the menu. Lucy Stone intends to discover who left Metinnicut Indian activist Curt Nolan dead with an ancient war club next to his head. If Lucy is not careful, she just may find herself served up as a last-minute course. Excerpt Chapter One "Look at that face. I ask you. Is that the face of a cold- blooded killer? In her usual seat in the second row, part-time reporter Lucy Stone perked up. Until now, she'd been having a difficult time paying attention at the Tuesday afternoon meeting of the Tinker's Cove Board of Selectmen, even dozing off for a few moments during the town assessor's presentation of the new valuation formulas. Lucy studied the face in the photograph Curt Nolan had propped up on an easel in the front of the hearing room, allegedly the face of a multiple killer: big brown eyes; an intelligent expression; a friendly, if somewhat toothy, smile. He didn't look like a mass murderer to her--he looked like a plain old mutt. "Kadjo's not just some mutt," continued Curt Nolan, his owner and advocate at the dog hearing. "He's a Carolina dog. I went all the way to North Carolina to get him from a breeder there. He's descended from the dogs that accompanied humans across the Bering land bridge from Asia to America thousands of years ago. He's a genuine Native American dog." He paused for emphasis and then concluded, "Why, he's got more tight to be here than you do." That comment was aimed at Howard White, chairman of the board of selectmen, who was chairing the dog hearing. White--a tall, thin, distinguished-looking man in his early sixties--didn't much like it and glared at Nolan from behind the bench where he was sitting with the four other selectmen as judge and jury. This was more like it, thought Lucy, studying Nolan with interest. Most people, when called before the board for violating the town's bylaws, exhibited a remorseful and humble attitude. Nolan, by contrast, seemed determined to antagonize the board members, especially Howard White. Even his clothing declared he was different from the majority of people who resided in the little town of Tinker's Cove, Maine. Instead of the usual uniform of khaki slacks, a button-down shirt, and loafers, which was the costume of choice for board meetings, Nolan was wearing a fringed leather jacket, blue jeans, and cowboy boots. His glossy black hair was brushed straight back and tied into a ponytail with a leather thong. A second leather thong, this one decorated with a bear claw, hung from his neck. His face was tanned and deeply creased, as if he spent a lot of time outdoors in the sun. "We're not interested in the animal's bloodlines," growled White. "We're here to decide if he's a threat to the community. I'd like to hear from the dog officer." Cathy Anderson stepped to the front of the room and con- suited a manila folder containing a few sheets of paper. Lucy had struck up an acquaintance with Cathy over the years and knew she hated speaking in public, even in front of the handful of citizens who regularly attended the selectmen's meetings. Cathy flipped back her long blond hair and nervously smoothed the blue pants of her regulation police uniform. That uniform didn't do a thing for her well-upholstered figure, thought Lucy. "The way I see it," said Cathy, taking a deep breath, "the problem isn't the dog--it's the owner." Hearing this, White exchanged a glance with Pete Crowley. Crowley was a heavyset man who tamed his thick white hair with Brylcreem so that the comb marks remained permanently visible. Also a board member, Crowley was Police Chief Oswald Crowley's brother and a strict hw-and-order man. "Mr. Nolan has refused to license the dog," continued Cathy, "in clear violation of state and town regulations. He also lets the dog run free, which is a violation of the town's leash law. If the dog were properly restrained we could avoid a lot of these problems." Crowley beamed at her and nodded sympathetically. "Can I say something?” Nolan was on his feet. Without waiting for permission from White, he began defending his pet. "Like I told you before, Kadjo is practically a wild dog. lie's closely related to the Dingo dogs of Australia and other wild breeds. He needs to be free--it'd be cruel to tie him up. And licensing him? That's ridiculous! We don't license bear or moose or deer, do we?” "You're out of order!" White banged his gavel, startling his fellow board member Bud Collier. Collier, a retired gym teacher, slept through most board meetings, rousing himself only to vote. Lucy often debated with herself whether she should mention this in her stories for the paper, but so far she had refrained. He was such a nice man, and so popular with the townsfolk, that she didn't want to embarrass him. Nevertheless, she wasn't entirely comfortable about covering up the truth. "Ms. Anderson has the floor," said White, raising a bristly white eyebrow. "Please continue." "Thank you." Cathy glanced at Nolan and gave him an apologetic little smile. 'Td like to call a witness, if that's all right with the board." White nodded. “I’d like to call Ellie Martin, who lives at 2355 Main Street Extension. Ellie, would you please tell the board members what happened last Monday?" Ellie Martin stood up, but remained by her chair in the rear of the room. She was a pleasant-looking woman in her forties, neatly dressed in a striped turtleneck topped with a loose-fitting denim jumper. She was barely five feet tall. "We can't hear you from there," said White. "Step down to the front." Clutching her hands together in front of her, Ellie came forward and stood next to Cathy. "Just tell them what happened," prompted Cathy. "I don't want to make trouble," began Ellie, glancing back at Nolan. "I only filed the report because I want to get the state chicken money." "What state money is this?" demanded board member Joe Marzetti. Owner of the IGA and a stalwart of the town Republican committee, Marzetti was strongly opposed to government spending. "It's to reimburse people whose livestock has been destroyed by dogs," explained Cathy. "It's actually town money mandated by state law--it comes out of the licensing fees." "But you said Nolan hasn't licensed the dog." Lucy resisted the urge to roll her eyes. Trust Marzetti to find an excuse--any excusemthat would save the town a few dollars. "That doesn't matter," said Cathy. "It's a state law." "Well if it's a law, how come I never heard of it?” Marzetti had furrowed his forehead, creating a single fierce black line of eyebrow. "Well, it hasn't come up in a long time. Not many people bother to keep chickens or sheep these days." "What kind of money are we talking here--how much are the taxpayers going to have to cough up?" "Thirty dollars." “Thirty dollars for a chicken!" Marzetti's face was red with outrage. "Why, I sell chickens for a dollar nine a pound in my store! That's ridiculous." "Thirty dollars total," said Cathy. "Mrs. Martin had a dozen hens and she'll get two dollars and fifty cents for each one." "Oh, that's more like it," said Marzetti. "The dog killed the chickens? Is that what this is about?" demanded Pete Crowley, who was growing impatient. "You'd better tell them," said Cathy, giving Ellie a little nudge. "Well, it was like this," began Ellie. "I was busy inside the kitchen, cleaning the oven, when I heard an awful commotion in the yard outside. I went to look and saw the dog, Kadjo, chasing the chickens. They're nice little pullets, Rhode Island Reds. I raised them myself from chicks I got last spring. They'd just started laying and I was getting five or six eggs a day. That is, I used to. The dog got every one." Ellie's face paled at the memory. "It was an awful sight." Lucy Stone

Our Past Week of Fresh Picks

It’s a thin line between love and love-hating. Katie Vaughn has been burned by love in the past—now she may Read More »

There are no rules this cruel summer…“I think we should see other people…” That one sentence unravels Samantha Parker&rsquo Read More »

THE DEATH MASK From #1 New York Times bestselling author Iris Johansen comes a new thriller starring Eve Duncan as she races against time to protect her beloved Read More »

Set in the art world of 1970s London, The English Masterpiece is a fast-paced read to the end, full of glamour and Read More »

Detective Arkady Renko—“one of the most compelling figures in modern fiction” (USA TODAY)—returns in this tense thriller set amid Read More »

Eat Post Like is a heartwarming debut novel of self-discovery, resilience, and the transformative power of food.Cassie Brooks has her life all Read More »

In this million-copy international bestseller from Korea, the owner of a corner store takes in an unhoused man who does a good deed, a Read More »

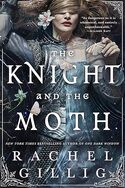

From NYT bestselling author Rachel Gillig comes the next big romantasy sensation, a gothic, mist-cloaked tale of a young prophetess forced Read More » |

|

| |||

|

||||

Sweet, Slow Burn Set in Scenic Key West

Sweet, Slow Burn Set in Scenic Key West

© 2003-2025

© 2003-2025