BONEY CREEK |

|

Berkley From the author of The Accidental Bestseller

comes a wonderfully entertaining book about what to do when

life comes at you full swing. Excerpt Well bred girls from good Southern families are not supposed to get shot. Vivien Armstrong Gray’s mother had never come out and actually told her this, but Vivi had no doubt it belonged on the long list of unwritten, yet critically important rules of conduct, on which she’d been raised. Dictates like, ‘always address older women and men as Ma’am and Sir’, ‘never ask directly for what you want if you can get it with charm, manners or your family name.’ And one of Vivien’s personal favorites, ‘although it’s perfectly fine to visit New York City on occasion in order to shop, see shows and ballet, or visit a museum, there’s really no good reason to live there.’ Vivien had managed to break all of those rules and quite a few others over the last forty-one years, the last fifteen of which she’d spent as an investigative reporter in that most Yankee of cities. The night her life fell apart Vivi wasn’t thinking about rules or decorum or anything much but getting the footage she needed to break a story on oil speculation and price manipulation that she’d been working on for months. It was ten PM on a muggy September night when Vivien pressed herself into a doorway in a darkened corner of a Wall Street parking garage a few feet away from where a source had told her an FBI financial agent posing as a large institutional investor was going to pay off a debt-ridden commodities trader. Crouched beside her cameraman, Marty Phelps, in the heat-soaked semi-darkness Vivien tried to ignore the flu symptoms she’d been battling all week. Eager to finally document the first in a string of long awaited arrests, she’d just noted the time—10:15PM—when a bullet sailed past her cheek with the force of a pointy-tipped locomotive. The part of her brain that didn’t freeze up in shock, realized that the bullet had come from the wrong direction. Marty swore, but she couldn’t tell if it was in pain or surprise, and his video camera clattered onto the concrete floor. Loudly. Too loudly. Two pings followed, shattering one of the overhead lights that had illuminated the area. Heart pounding, Vivien willed her eyes to adjust to the deeper darkness, but she couldn’t see Marty, or his camera, or who was shooting at them. Before she could think what to do, more bullets buzzed by like a swarm of mosquitoes after bare flesh at a barbecue. They ricocheted off concrete, pinged off steel and metal just like they do in the movies and on TV. Except that these bullets were real and it occurred to her then that if one of them found her, she might actually die. Afraid to move out of the doorway in which she cowered, Vivien turned and hugged the hard metal of the door. One hand reached down to test the locked knob as she pressed her face against its pock-marked surface, sucking in everything that could be sucked, trying to become one with the door, trying to become too flat, too thin, too ‘not there’ for a bullet to find her. Her life did not pass before her eyes. There was no highlight reel-- maybe when you were over forty a full viewing would take too long?--no snippets, no ‘best of Vivi’, no ‘worst of’ either, which would have taken more time. What there was was a vague sense of regret that settled over her like a shroud making Vivi wish deeply, urgently, that she’d done better, been more. Maybes and should haves consumed her; little bursts of clarity that seized her and shook her up and down, back and forth like a pit bull with a rag doll clenched between its teeth. Maybe she should have listened to her parents. Maybe she would have been happier, more fulfilled, if she hadn’t rebelled so completely, hadn’t done that expose’ on that democratic senator who was her father’s best friend and political ally, hadn’t always put work before everything else. If she’d stayed home in Atlanta. Gotten married. Raised children like her younger sister, Melanie. Or gone into family politics like her older brother, Hamilton. If regret and dismay had been bullet proof, Vivien might have walked away unscathed. But as it turned out, would’ves, should’ves, and could’ves were nowhere near as potent as Kevlar. The next thing Vivien knew, her regret was pierced by the sharp slap of a bullet entering her body, sucking the air straight out of her lungs, and sending her crumpling to the ground. Face down on the concrete, grit filling her mouth, Vivien tried to absorb what had happened and what might happen next as a final hail of bullets flew above her head. Then something metal hit the ground followed by the thud of what she was afraid might be a body. Her eyes squinched tightly shut, she tried to marshal her thoughts, but they skittered through her brain at random and of their own accord. At first she was aware only of a general ache. Then a sharper, clearer pain drew her attention. With what clarity her befuddled brain could cling to, she realized that the bullet had struck the only body part that hadn’t fit all the way into the doorway. Modesty and good breeding should have prohibited her from naming that body part, but a decade and a half in New York City compelled her to acknowledge that the bullet was lodged in the part that she usually sat on. The part on which the sun does not shine. The part that irate cab drivers and construction workers, who can’t understand why a woman is not flattered by their attentions, are always shouting for that woman to kiss. Despite the pain and the darkness into which her brain seemed determined to retreat, Vivi almost smiled at the thought. There were shouts and the pounding of feet. The concrete shook beneath her, but she didn’t have the mental capacity or the energy to worry about it. The sound of approaching sirens pierced the darkness—and her own personal fog-- briefly. And then there was nothing. Which at least protected her from knowing that Marty’s camera was rolling when it fell. That it had somehow captured everything that happened to her--from the moment she tried to become one with the door to the moment she shrieked and grabbed her butt to the moment they found her and loaded her face down onto the stretcher, her derriere pointing upward at the concrete roof above.

Our Past Week of Fresh Picks

A serial killer stalks a small town, and a police officer must face her family’s dark past to catch him.The sleepy community Read More »

She took on titans, battled generals, and changed the world as we know it…New York Times bestselling author Stephanie Dray returns with a Read More »

LIMITED FIRST PRINT RUN--ALL first edition copies will be signed by the author! Signed copies available only for a limited time and while supplies Read More »

It’s a thin line between love and love-hating. Katie Vaughn has been burned by love in the past—now she may Read More »

There are no rules this cruel summer…“I think we should see other people…” That one sentence unravels Samantha Parker&rsquo Read More »

THE DEATH MASK From #1 New York Times bestselling author Iris Johansen comes a new thriller starring Eve Duncan as she races against time to protect her beloved Read More »

Set in the art world of 1970s London, The English Masterpiece is a fast-paced read to the end, full of glamour and Read More »

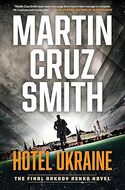

Detective Arkady Renko—“one of the most compelling figures in modern fiction” (USA TODAY)—returns in this tense thriller set amid Read More »

|

|

| |||

|

||||

A Gripping Thriller That Blends Police Procedural, Psychological Drama, and Non-Stop Action

A Gripping Thriller That Blends Police Procedural, Psychological Drama, and Non-Stop Action

© 2003-2025

© 2003-2025