CRUEL SUMMER |

|

Summer of love and chickens

Harper Teen What happens when a city girl is transplanted onto a

ramshackle organic farm in the middle of nowhere?

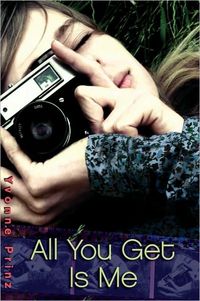

Everything. Excerpt Thirteen black and white photos of the accident hang across the clothesline in my dark room like crime scene laundry. The last one is still in the developing solution. I push it around with the rubber tipped bamboo tongs as the image comes into focus. It's the overturned SUV resting in the middle of the asphalt road. In the upper right hand corner an unintentional piece of the ambulance with its back doors open appears. I must have taken it right after the paramedics loaded the stretchers. Sylvia Hernandez's bare foot is clearly visible. You can also see part of her other foot, which somehow still has a pristine white sneaker on it. I remove the print from the developer and drop it in the stop bath. I can't take my eyes off Sylvia's foot. Next to the accident photos are the rest of the photos from the roll, a Buddhist monk with a shaved head eating a wedge of melon, a young smiling monk holding a puppy, Steve, trying to hypnotize a chicken, a three-legged dog. I took them the day Steve and I drove over to the Monastery not far from here. We had fun that day. Sylvia is in a box on a plane right now. She's flying home to her family in a small village in Mexico where she'll be buried in a tiny graveyard full of flowers. If the Mexicans are right about what happens after you die, she's already in heaven. I hope they know what they're talking about for Sylvia's sake. Tomas, her husband, won't be attending the funeral. It's far too risky for Tomas to cross the border into Mexico. Who knows if he'll ever make it back? My dad talked to Tomas's employer, a factory farmer near here who plants Genetically Modified seeds from Monsanto. He grows corn, only corn, as far as the eye can see. He gets his laborers from a contractor who brings them in on horrible crowded trucks like cattle. All of them, like Tomas and Sylvia, are part of an illegal work force that people around here don't like to think about too much. They work cheap and they don't expect benefits. My dad asked the farmer if Tomas could have a few days off to deal with his affairs. Tomas is a good worker so he said he'll probably take him back but he couldn't promise anything. Why should his production suffer just because someone's wife died, he reasoned. Besides, according to his records, Tomas doesn't even exist. Rosa, the baby, is being sent to her grandparents in Mexico now because Tomas could never manage to take care of her here. He has no home here to speak of. Sylvia has a sister here too, Wanda, but she's also a farm laborer with two kids back at home in Mexico. I'm not sure who's taking care of them but I sure hope someone is. Sylvia was a housekeeper and a nanny for the Thompsons who live in a development called Orchard Hill. It used to be a fruit orchard but pretty much all the trees had to be cut down to build the houses. There doesn't seem to be a hill anywhere either. When the accident happened, Sylvia had just dropped two of the Thomson kids off at a summer day camp and she was on her way home to clean the house before it was time to pick them up again. People around here who knew her say she was a happy person and a good, honest worker. You would think that they'd be able to come up with something better than that. Does anyone really want to be remembered as a good, honest worker? I seriously doubt it. I'm sure she would prefer something like: Sylvia loved to dance and had a wonderful singing voice. She loved her baby, Rosa, and hoped to send her to school in America one day. The smell of corn tortillas made her terribly homesick and the sound of Mariachi music on the radio made her cry. She looked great in red and owned three red skirts. When she smiled at you her face lit up and it was impossible not to smile back. Something like that. From inside my darkroom I can hear Steve or Miguel starting up the tractor, drowning out Bruce, our highly dysfunctional rooster who crows almost all day long. He has a determined look on his face like he's misplaced something important like his keys and he'll spend entire days scratching in the dry dirt looking for them. When he stops crowing for a while I find myself waiting for it. Aaaah, farm life. My darkroom is an old supply shed with blankets nailed over the windows that my dad built for me to fulfill a contractual agreement we arrived at on the day we left the Noe Valley house for good. He told me that if I let go of the banister and got in the car, he would build me a darkroom on the farm. Of course I needed that in writing. Parents are often full of empty promises when they want to motivate you and I needed a completion date for this alleged dark room. I am, after all, the daughter of a lawyer. Before I got in the car I went up and down the street and delivered an index card with our new address and phone number to each of our neighbors just in case my mom came looking for us. They all looked at me like I was a sad orphan, which made me feel slightly better about the fact that I was getting away from this place where everyone knew at least part of my story.

My dad stuck to the contract. He insulated the shed and put in an old sink. He bought some used kitchen cabinets for storage and Formica countertops at a salvage place to set a used Bezzler enlarger on. It's pretty rustic but it's my first dark room so I can't complain too much. My dad has been on the phone all morning with the police and his lawyer friend, Ned. He's hell bent on making sure the woman who killed Sylvia (and walked away with a few scratches and a concussion) is charged. Miguel and Steve keep shaking their heads doubtfully. Steve told me that a rich white woman who hits an illegal Mexican immigrant with her car is likely never even going to hear about it again. If the roles were reversed it would be a different story entirely. Sylvia would already be in prison. Well, my dad says that if she isn't charged he'll file a civil suit on behalf of her family but Miguel isn't even hopeful about that. He says that the family won't want to stir up trouble and risk losing their jobs. The Mexican people have a whole different take on death. They seem to view it as the other half of life. Not something to be feared. My favorite holiday when we lived in Noe Valley was the Day of the Dead, which happens every year right after Halloween. My mom and dad and I would walk down the hill to the Mission and buy sugar skulls at the bakery on 24th street and then we'd watch the parade of dancing skeletons and musicians and all sorts of ghoulish creatures go by. The idea is that the dead are gone but not forgotten. People wear pictures of their departed on a string around their necks and they build altars in their living rooms filled with candles and flowers and their dead relatives favorite snack foods and drinks and cigarettes. It's a huge party with Death as the theme. It's awfully cool. I've got a ton of pictures I've taken in a box somewhere. When the photos dry I pull them off the clothesline and put them in a stack. I click off the red light and pull open the wooden door. Bright sunlight streams in and I squint like a hamster. Steve is planting arugula seedlings that were started in the green house into one of our "small gardens". These are special raised gardens that are replanted all summer long so we always have fresh baby lettuces. "Hey," I call out as I walk past him. He lifts the wide brim of his straw sun hat. "Hey Roar. Whatcha got there?"

"Photos of the accident for my dad." "Lemme have a look." He stands up. I walk over and hand him the stack. He takes them in his filthy hands and flips through them, shaking his head. He stops at the one of the overturned SUV. "Hey, I know that SUV. That woman is mucho uptight. She went off on me the other day when I double-parked in front of Millie's for a nanosecond to deliver eggs. "Yeah, we kind of got that impression too." He hands the photos back to me. "Good CSI work, pal."

"Yeah, thanks. She probably won't even get charged." I squint up at him. Steve's about six feet tall. "Nah, but what a load of bad karma." "You believe in that stuff?" I ask. "Sure. There's the criminal justice system, which isn't worth a hill of beans in this country unless you're white and rich and then there's karmic justice, which is part of the natural order of the universe." I nod. It makes sense to me. "Yeah. I suppose I believe in it too." My mom was a believer. She always told me that bad karma catches up with you when you're least expecting it. She also told me that if you were cruel to animals you'd come back as one in your next life. I pointed out to her that Mittens, the cat who spent hours in her lap, could really be a bully who tied firecrackers to cat's tails. She thought about this and then she never said anything about it again. I felt like a real killjoy for stepping all over her theory.

Steve arches his back and bends over to touch his toes. I stand there feeling stupid. He straightens up again and takes off his hat and runs his fingers through his coarse wavy red hair. He puts his hat back on and looks over at the house. "Tell your dad I'm going to need some help loading the truck for the market later." "Okay." "You gonna work it with me?" he asks.

Our Past Week of Fresh Picks

THE DEATH MASK From #1 New York Times bestselling author Iris Johansen comes a new thriller starring Eve Duncan as she races against time to protect her beloved Read More »

Set in the art world of 1970s London, The English Masterpiece is a fast-paced read to the end, full of glamour and Read More »

Detective Arkady Renko—“one of the most compelling figures in modern fiction” (USA TODAY)—returns in this tense thriller set amid Read More »

Eat Post Like is a heartwarming debut novel of self-discovery, resilience, and the transformative power of food.Cassie Brooks has her life all Read More »

In this million-copy international bestseller from Korea, the owner of a corner store takes in an unhoused man who does a good deed, a Read More »

From NYT bestselling author Rachel Gillig comes the next big romantasy sensation, a gothic, mist-cloaked tale of a young prophetess forced Read More »

It’s twice as hot in this extra steamy Christmas in July two-in-one cowritten by #1 New York Times bestselling Read More »

Three best friends turn to murder to collect on their husbands’ life insurance policies… But the husbands have a plan of their own Read More » |

|

| |||

|

||||

Another amazing thriller!

Another amazing thriller!

© 2003-2025

© 2003-2025