CRUEL SUMMER |

|

A vampire rises to power. A woman finds her destiny.

Avon A March 1862. The misty, moody, rain-lashed moors. A scrounge of mysterious deaths. A child in peril. A manor house with strange Latin inscriptions that look like clues. An inscrutable handsome stranger whose motives are unclear. A fraught relationship between sisters. A secret family heritage that will change one woman's life forever, and give the world one slim chance to vanquish an ancient and undreamt-of evil. Plus: vampires. A bunch of them. And a hint of the most powerful vampire of all: The Dracula. When young Victorian widow Emma Andrews travels to her cousin's country manor, she expects it to be an ordinary family visit. Instead, she will discover she has hidden powers, meet a mysterious stranger, battle a menacing evil--and change the direction of her life forever. Excerpt I was twenty-three years of age in March of 1862 when I traveled to my cousin’s home in the countryside of Wiltshire. The fifth day of that wretched month found me huddled in my carriage, the drizzly gray gloom outside soaking a bone-deep chill into every aching part of my body, which had been roughly abused by the long confinement and ill-kept roads over which I’d traveled coming up from Dartmoor. I did not know then that these would be the closing days of ordinary life. The only suggestion of the monumental changes that were about to occur was the headache that had come upon me upon crossing the Dart River. The pain, as fine as tiny needles being pushed into my temples, increased as I crossed the chalk downs and approached Dulwich Manor. At the time, I assumed this was due to anxiety, for my younger sister and her new husband were among the guests invited for an extended stay at my cousin’s sprawling country house. As I was long accustomed to contending with Alyssa without anything like this haunting megrim, I suppose I should not have made this rather obvious misattribution. But how could I have thought differently, back then? The house was a large, ugly thing, squatting low on the land like a spider on a softly rounded hilltop. Stones blacked with lichen and soot formed a plain rectangle of unadorned walls dotted liberally with cross-hatched windows, lying dormant under leaden skies. There were no signs of life about it or any of the outbuildings. Everyone had taken shelter from the rain. I emerged into a light drizzle and drew the cowl of my cloak over my head. At the top of the impressive set of carved steps a very correct looking servant waited. “Emma Andrews, Mrs. Dulwich’s cousin,” I told him. He did not quite meet my gaze, as all good servants manage not to do, as he opened the door wider and ushered me inside to a vaulted hall. I was instantly struck by the feeling of being very, very small in a very, very large place. The gasjets on the wall leaked only a small puddle of light in which I stood, beyond which I saw only shadowy hints of the rest of the room. “I shall tell madam you have arrived,” the manservant intoned soberly. Once alone, I quickly checked my appearance in a pier glass hung on the wall. I was decidedly damp. My hair was nearly a ruin. The expensive gown I had donned that morning, thinking it would lend me courage, had been a bad choice. There was nothing to be done about the crushed silk. A smart travel dress would have been better, had I owned one. But such things required seamstress consultations and fittings, all amounting to too much time, time I never seemed to make room for in my ordinary routines. I did take comfort in the fine brushed wool of my cloak which Simon, my husband, had given me for Christmas last year, a month before he died. It was of excellent quality. A voice brought me up sharp. “I am most put out that the weather is foul,” my cousin, Mary, said as she swept into the hall. “I wanted to show the house to its full advantage.” She posed regally in the hall of the Jacobean house, her pride radiating from her. She knew her surroundings elevated her, as wealth is apt to do. She had married well and that is always a woman’s conceit. And yet, it had not been mine. My late husband, Simon, had left me his wealth, something I found made my rather ordinary life a bit more convenient than it had previously been, but little else had changed because of it. I certainly took no pride in showing it off. “The house is magnificent, Mary. I am anxious to see what you have done with its restoration. It seems very grand indeed.” That pleased her, thawed her a bit. She cocked her chin at me and turned slightly so that I might press a kiss upon her cheek in a rather pretentious gesture for a woman only three years my senior. But I complied. I have no trouble indulging others’ vanities, if they are harmless. “Come then, Emma,” she said, “the parlor is through here. Give Penwys your cloak. Alyssa and Alan have already arrived. I know she is anxious to see you. Penwys will see your things are delivered to your room and the servants will put everything to rights. You can go upstairs when you’ve met everyone and freshen up then.” She was showing off a bit, taking on the same airs Alyssa was so fond of. As just as with my sister, they had the tendency to prick my sore spot and made me wicked. “Oh, very well,” I conceded, “but please direct your man to be very careful with my portmanteau. It is old, and I take extra care of it since it had been my mother’s.” The mention of Laura—my beautiful, tragic mother— changed her expression to one rife with thoughts best left unsaid. “Your belongings will be treated with the respect they deserve.” We proceeded together down a short corridor. Above, a series of large arches stretched across the high ceiling like ribs, giving me the unsettling feeling of traversing the interior of a vast corporeal chest. My eye was caught by some words carved at the apex of the last of these stone vaults, just above the heavy double doors beyond which I could hear the muffled sounds of conversation. An odd place for decoration, I mused. It would be easily overlooked as it was placed high overhead. But I could read the three words. Corruptio optimi pessima. I stopped. Something strange and unpleasant fluttered through me. The air went crisp, as if ionizing in preparation for an electrical strike. Mary saw me staring. “Interesting, isn’t it? Those carvings are all over the house. The man who built the original manor was a bishop, back before Henry, when the papists still had the run of the place.” She laughed. “It’s a curiously religious dwelling as a result, and I’ve kept it that way through the restoration. These ominous sayings carved here and there are terribly quaint, don’t you agree?” My voice was dry as dust. “Do you know what it means?” She must have forgotten my unfortunate habit of overburdening my brain with reading, for she thought I didn’t know. “I believe it means ‘the best of men are incorruptible.’” It did not. The fact that she didn’t know made my uneasiness grow. It felt to me—very strongly so—that it should be important the owner of this house understand what was written into its very bones. The correct translation was “Corruption of the best is worst.”

Our Past Week of Fresh Picks

THE DEATH MASK From #1 New York Times bestselling author Iris Johansen comes a new thriller starring Eve Duncan as she races against time to protect her beloved Read More »

Set in the art world of 1970s London, The English Masterpiece is a fast-paced read to the end, full of glamour and Read More »

Detective Arkady Renko—“one of the most compelling figures in modern fiction” (USA TODAY)—returns in this tense thriller set amid Read More »

Eat Post Like is a heartwarming debut novel of self-discovery, resilience, and the transformative power of food.Cassie Brooks has her life all Read More »

In this million-copy international bestseller from Korea, the owner of a corner store takes in an unhoused man who does a good deed, a Read More »

From NYT bestselling author Rachel Gillig comes the next big romantasy sensation, a gothic, mist-cloaked tale of a young prophetess forced Read More »

It’s twice as hot in this extra steamy Christmas in July two-in-one cowritten by #1 New York Times bestselling Read More »

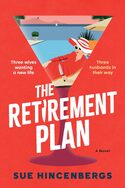

Three best friends turn to murder to collect on their husbands’ life insurance policies… But the husbands have a plan of their own Read More » |

|

| |||

|

||||

© 2003-2025

© 2003-2025