CRUEL SUMMER |

Fall headfirst into July’s hottest stories—danger, desire, and happily-ever-afters await. |

Purchase

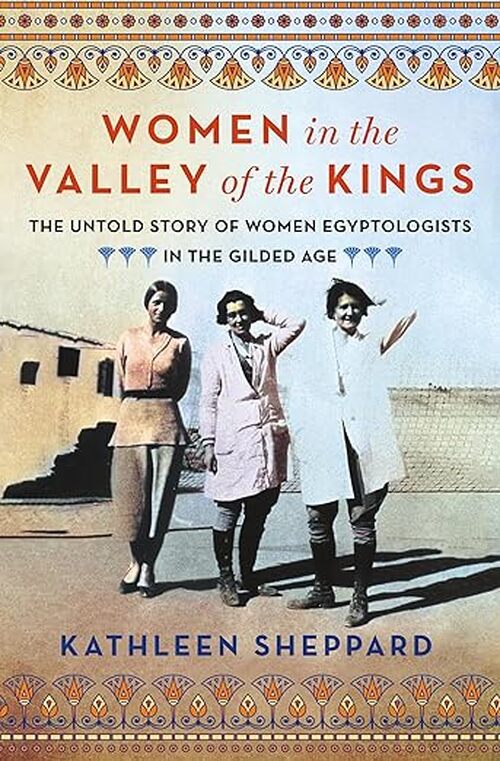

St. Martin's Press Non-Fiction Biography, Multicultural Excerpt of Women in the Valley of the Kings by Kathleen SheppardCopyright © 2024 by the author and reprinted with permission of St. Martin’s Publishing Group.

Prologue: A New Golden Age Our story begins not with Napoleon in 1798 but in 1873, with the earliest British women who ventured to Egypt as travelers. Amelia Edwards and Marianne Brocklehurst went to Egypt in search of something—health, sunshine, a life’s purpose—and they found

to travel by Lucie Duff Gordon’s Letters from Egypt. These letters from a lonely woman who had tried to find fresh, dry air for her tuberculosis-ridden lungs inspired countless women and men to travel to Egypt. Amelia and Marianne both established institutions that soon became centers of the burgeoning discipline of Egyptology in Britain. As we dig down into their stories, the timeline of activity and opportunity reveals itself like a new stratigraphic layer each time. As each won her own battles, she set up the women who came later. Because of Amelia and Marianne, women in Britain like Maggie Benson and Nettie Gourlay were able to be educated in Egyptology, and they worked together to do their own excavations while battling issues of oppression and exclusion. Emma Andrews’s incredible success as a patron and archaeologist both depended on Maggie and Nettie’s work and helped pave the way for Margaret Murray to teach women to go into the field. Margaret’s work in the university department that Amelia Edwards created allowed the artists Myrtle Broome and Amice Calverley being on-site, where they used their abilities to create brilliant reproductions of the art on the walls of the Temple of Seti I at Abydos. Amelia Edwards’s influence and money also resulted in Kate Bradbury and Emily Paterson, as well as Caroline Ransom, having leadership positions in central institutions, both small and large.

Women led the field of Egyptology in a number of ways despite and sometimes because of the obstacles men put in their way. Each new step, professionally, broke barriers for the next generation. Barred from education, they traveled, experienced, learned, and wrote about Egypt in ways they couldn’t do in a classroom. Excluded from field training, they found opportunities to be present and excavate on their own. Prohibited from theorizing or imagining at the site, they re-created Egyptian art in astounding and wonderful ways. Forbidden from being allowed to find the artifacts, they acquired, organized, and maintained the world’s largest and most important collections.

It is because of these women that we have the legacies of richly illustrated travelogues, of valuable excavation seasons on sites that had been deemed unimportant, of long-lost beautiful murals copied and presented in books for future scholars to learn from, of great collections in famous museums and foundational research institutions that survived and thrived during wartime and depression. Women were, in fact, the reason that any of the “Great Men” of Egyptology were able to be “Great” at all.

Frequently, these women worked in tandem with Egyptians, too. Both groups understood their usually subservient role to the Great Man on-site. But their work—excavating, training, guarding, funding, and selling pieces—made sure the European and American men were successful in the field. Egyptian workers appear alongside these women throughout the story of early Egyptology, likewise fighting for inclusion. Egyptians are not as well-known historically as Western women (which is really saying something), and their stories in the archives and published sources are virtually nonexistent, so their stories will be centered and significant, however small. As the story here unfolds, we will meet and follow men such as excavators, dahabeah captains, guides, ru’asa (excavation foremen), consuls, and dealers. Their accomplishments run through this history like a central thread that, if left out, would unravel the rich and varied tapestry of the story.

Women in the Valley of the Kings presents a new idea of a Golden Age, defined not by what men did politically but by the arrival of women on their own terms, beginning with Amelia Edwards’s journey in 1873 and ending with Caroline Ransom Williams’s death in

cause us to rethink the era and ask questions like: For whom was this age golden? What roles did women play in building and maintaining the colonial structures in Egypt? When, how, and by whom were Egyptians finally allowed to participate in the study of their own ancient remains? Make no mistake, these women still took artifacts during this so-called Golden Age, but their main disciplinary work was more constructive and sustainable, and less destructive, than men’s work.

The women in this volume came to Egyptology because of a love for the ancient monuments, the people, and their history, not to mention the mystery of it all. For the most part, women’s work in the field happened at different times and in different spaces than men’s. Western women arrived in Egypt later than men did. Once they were in-country, their focus tended to be more on experience, travel, and preservation of material remains than discovery, although several women did uncover a number of important sites and artifacts. While they worked both on-site and off, women often used their money, influence, and expertise to create, support, and maintain institutions instead of spending most of their time excavating in the field. The discipline of Egyptology, therefore, looks different when women dominate the field. Based on their work as artists, diarists, and collectors, these women will be called Egyptologists. Based on their jobs in university classrooms, home museum collections, and disciplinary societies, Egyptology will be defined as building institutions and not deconstructing sites. Egyptology will finally be seen as women’s work.

There are many different definitions of Egyptology, and even more that try to simultaneously carve out a definition of a “Golden Age” of the discipline. Egyptology could comprise the “wonderful things” to which the famous British archaeologist Howard Carter referred when he was asked what he saw as he first peered through the dark and dust into Tutankhamun’s almost undisturbed tomb. Egyptology could include the wide public interest in Egypt’s history that trailblazer Amelia Edwards said “never flags” in those who truly love Egypt. It could be the study and mastery of the ancient script of the people who walked, talked, lived, and loved in Egypt five thousand years ago. It could be the study of their remains, with the discerning mind put to solving the questions and problems that continually arise with new finds. It very well is all of these things.

The term ancient Egypt, usually designated as the period from around 3250 BCE to the arrival of Alexander the Great in 332 BCE at the end of the Late Period, commonly defines the general era studied by people who call themselves Egyptologists. The Greco-Roman period is a separate period, but is still considered Egyptology, beginning in 332 BCE and ending with the death of the final Ptolemaic ruler, Cleopatra VII, in 30 BCE. That does not mean that other periods and topics of Egyptian history do not matter—in fact, the geology, climate, economy, politics, and anthropology of Egypt matter a great deal. It is simply that those topics are not usually considered to be part of Egyptology, specifically. The study of many of the Egyptian scripts—at any point on the ancient timeline—is often understood as Egyptology. The search for, excavation of, and study of the material remains of ancient Egyptian civilization are usually understood as Egyptian archaeology, the discerning factor between the two being the focus on and comprehension of ancient scripts. Egyptian archaeologists can be Egyptologists and vice versa; it certainly helps to be both.

The term “Golden Age” of this discipline is also up for some debate. Typically, “Golden Age” refers to the period defined by the common Grand Narrative, from the coming of Napoleon and the French in 1798 to the finding of King Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922. It is a period in which wealthy, white Europeans and Americans ran rampant over the cultural heritage of a colonized country and its people, vandalizing and pillaging as they went. To be clear, the 130 or so years of European dominance in Egypt was a “Golden Age” for the Western study of Egyptology because neither the laws in place at the time nor the cultural norms put in place by the Western rulers stopped this looting behavior—in fact, the laws actually encouraged violence and oppression by allowing the men and women who came to Egypt to take what they wanted, with impunity, and reasonably expect to be safe and remain unmolested while doing it.

Writing mostly about Western women without acknowledging their role in the colonized history of Egyptology doesn’t reflect the true story. These women were part of the colonizing institutions and were, therefore, colonizers themselves. The reality of the situation, however, is more complex because, for far too often, women and Egyptians were also the colonized. If one looks clearly at the accomplishments of the explorers in the following pages, one can see that they are the pillars on which the male heroes of Western Egyptology stood in order to rise to their lofty status. If we are to see the fascinating history of discoveries in Egypt clearly, we have to look at the women and prominent Egyptians who did the groundbreaking work among the pyramids and temples and place them where they really belong within the history of Egyptology—directly at the center. By finally acknowledging the accomplishments of these individuals, a more realistic picture of the history of the field and a truer, more inclusive definition of Egyptology emerge. Excerpt from Women in the Valley of the Kings by Kathleen Sheppard |

|

| |||

|

||||

© 2003-2025

© 2003-2025