EXTINCTION |

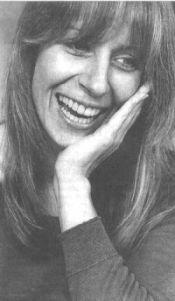

Sunshine, secrets, and swoon-worthy stories—June's featured reads are your perfect summer escape. | Penny Valentine

When the Beatles travelled to London to promote their early records, one of their ports of call was the office of Disc And Music Echo on Fleet Street. In the words of Andrew Loog Oldham, then acting as their press officer, they went to "ogle and fawn over" Penny Valentine, who had become Britain's most influential reviewer of new pop singles. Valentine was worth fawning over, then and for the remainder of her life, which ended last week at the age of 59 after a long struggle with cancer. In the 1960s she had lived up to the dolly-bird perfection of her improbably glamorous byline with a wardrobe of spectacular mini-dresses, and long blonde hair which required twice-weekly visits to Vidal Sassoon's Bond Street salon; she had a generosity of spirit and a gift for friendship that preserved her beauty through the years. Few journalists of a later generation who were taught by Valentine at Goldsmiths College and North London University, or those who joined her in a women's group or publishing collective, or even her younger colleagues at the Guardian during her last years, could have any real inkling of her past, which included genuine friendships with the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, who respected her taste and loved her company. She was probably the first woman to write about pop music as though it really mattered, and her appearances on television's Juke Box Jury made her one of the first "media teenagers". She was born of Jewish and Italian ancestry on St Valentine's eve in central London, the only child of a father employed in the old Covent Garden market and a doting mother whose several concurrent jobs included both hairdressing and office work. It was from their Bloomsbury flat that, at 16, Penny set out to become a trainee reporter on the Uxbridge Post. That led to a job at Boyfriend, a weekly magazine for teen girls, and from there she joined Disc. Ever present at the right clubs, parties and television studios, and a magnet of attention for young male pop stars (and, on one occasion, Steve McQueen), she nevertheless conveyed the impression that she was there at least as much for the music as for the social scene. She loved soul music, and campaigned on behalf of the likes of Aretha Franklin and Marvin Gaye when they were still on the margins of popularity. Her sharp ear enabled her to pick out future classics, and she had tipped David Bowie for success long before Space Oddity became a hit. Dusty Springfield was a friend, and Levi Stubbs, the voice of the Four Tops' Reach Out I'll Be There, taught her to dance. Although judicious, her opinions conveyed an unguarded enthusiasm. She was writing for the kids who bought and danced to the records, not for Tin Pan Alley. "It's a girl's song with incredibly feminine words," she wrote in a review of Rita Wright's I Can't Give Back The Love I Feel For You in 1968, "and I felt it so much I wanted to cry." In 1970 she left Disc to join the staff of Sounds, a new rival to the Melody Maker, but three years later she was hired by Elton John, another friend, to become the press officer for his new record label, Rocket. A spell at Anchor Records, which was another fledgling outfit, came next, followed by a year in New York. She returned to London in 1975 to help launch Street Life, a short-lived attempt to create a British equivalent of Rolling Stone. After the magazine failed she joined Time Out, contributing to the television section, and it was there that the second half of her life began. A socialist by instinct and a feminist by experience, she was one of the 34 members of staff who left the magazine in 1980, after a bitter and unsuccessful battle to preserve wage parity, and founded City Limits, where for seven years she honed her skills as an assistant editor. She was active in a number of bodies, including Women in Media, Sheba, a feminist publishing collective, Music For Socialism and the National Union of Journalists, of which she was a life member. After gaining a BA in film studies and English at North London Polytechnic, she pursued a freelance career which included teaching, working shifts at the Guardian and writing, with her old friend Vicki Wickham, a well received biography of Dusty Springfield, Dancing With Demons (2000). To the enduring bemusement of her admirers, however, she lacked any sort of confidence in her own writing. Briefly married in the early 1960s to Adrian Monteith, later that decade she began a long relationship with John Adrian, a record company executive. In 1973 she met Mike Flood Page, a fellow journalist who later became a television producer. They were together for 25 years and in 1982 she gave birth to their son, Dan. Her combination of Jewish pessimism and Italian passion did not always make the easiest basis from which to tackle life, but it did make her a ferociously loyal and considerate friend, if sometimes a noisy and bossy one. She faced her painful illness with courage, humour and an unexpected strain of optimism. Thinking back to her days as a cub reporter, she once said that if she ever wrote her autobiography, she would call it If Wet, In Church Hall. Something very much larger would be needed to hold all those fortunate enough to call themselves the friends of the woman who turned out to be as real as her name. - The Guardian obituary

Log In to see more information about Penny Valentine

SeriesBooks:Dancing with Demons, December 2001Paperback (reprint) |

|

|

| |||

|

||||

© 2003-2025

© 2003-2025